Materials in shrimp, fish, and algae combined to provide 192% More UV Protection Vs. Regular Sunscreens

A multinational team of researchers from Sweden, Spain, and Australia developed a novel biopolymer material by attaching ultraviolet-absorbing compounds found in fish and algae to chitosan, a biopolymer derived from shrimp shells. The material demonstrated the capability to provide 192% More Ultra Violet (UV) protection compared to commercially available sunscreens.

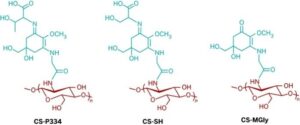

UV radiations have many detrimental effects in living organisms that challenge the stability and function of cellular structures. UV exposure also alters the properties and durability of materials and affects their lifetime. It is becoming increasingly important to develop new biocompatible and environmentally friendly materials to address these issues. Inspired by the strategy developed by fish, algae, and microorganisms exposed to UV radiations in confined ecosystems, we have constructed novel UV-protective materials that exclusively consist of natural compounds. Chitosan was chosen as the matrix for grafting mycosporines and mycosporine-like amino acids as the functional components of the active materials. In their study, the researchers demonstrated that these materials are biocompatible, photoresistant, and thermoresistant, and exhibit a highly efficient absorption of both UV-A and UV-B radiations. Thus, they have the potential to provide an efficient protection against both types of UV radiations and overcome several shortfalls of the current UV-protective products. In practice, the same concept can be applied to other biopolymers than chitosan and used to produce multifunctional materials. Therefore, it has a great potential to be exploited in a broad range of applications in living organisms and nonliving systems.

New materials containing ultraviolet-absorbing molecules (called, mycosporines) found in algae and fish fabricated with shrimp-derived chitosan was developed as nontoxic, biocompatible sunscreens (ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 10.1021/acsami.5b04064). The photo-resistant materials could be used in a variety of applications which can benefit from the benefits of UV protecton, such as cosmetics or as UV-protective coatings for outdoor furniture or clothing.

Commercial sunscreens contain two types of compounds to block both longwave UV-A light that may cause cancer and shortwave UV-B light that causes sunburn. Some fish, algae, and cyanobacteria produce amino acids called mycosporines that absorb both UV-A and UV-B light. To develop more effective, biocompatible sunscreens, some manufacturers have added mycosporines to their formulations. But free mycosporine molecules can diffuse through a smear of sunscreen, making it difficult for the UV-blocking agents to stay where they are applied.

Susana C. M. Fernandes and Vincent Bulone, of the Royal Institute of Technology, in Sweden, and their colleagues thought they might solve this problem by attaching the mycosporine molecules to a polymer. First, they activated the carboxylic acid portion of each of three mycosporines using the coupling agent N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N’-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride. Then the researchers attached each activated mycosporine to long chains of chitosan polymer. Chitosan is produced from chitin, a sugar polymer in crab, shrimp, and insect shells.

The new materials absorbed UV-A and UV-B light as effectively as the free mycosporines. The molar absorptivities of the three materials were 125 to 192% greater than that for ethylhexyl p-methoxycinnamate, a UV-B-absorbing ingredient in many current commercial sunscreens. Larger absorptivity values indicate greater UV protection, so these new materials could potentially be superior to current sunscreen ingredients, Bulone says.

The researchers then cast films from the new materials and found that the films were stable after exposure to 12 hours of UV light or temperatures of 80 °C. These properties may make the materials useful as UV-protective coatings for outdoor furniture or clothing, Bulone says.

Vijay Kumar Thakur of Washington State University, who was not involved with the work, says that because mycosporines are naturally occurring amino acids, they could be more biocompatible than current sunscreen ingredients. Indeed, Bulone and colleagues found that growing mouse fibroblasts on the films for three weeks resulted in little cell death. Thakur adds that chitosan has inherent antimicrobial properties, so he wonders if these new materials may be antimicrobial, as well.

In the U.S., the FDA have been slow to approve sunscreen ingredients due to the possible absorption and possible effects of the chemicals found in commercially available sunscreens. But Bulone thinks commercializing these new biopolymer materials could be relatively simple, since all the components—the mycosporines, chitosan, and the coupling reagent—are currently used in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, or medical products.